MEXICO CITY

ENCROACHMENT OF THE URBAN ON WATER

Mexico City has a historical and intrinsic relationship with water. The city is currently located in what used to be a collection of five great lakes of the Valley of Mexico: Laguna de Zumpango, Lago Xaltocan, Lago San Cristobal, Lago De Texcoco, Lago Xochimilco and Lago Chalco. These lakes were fed by the various volcanoes and mountain ranges that cradle them.

Founded by the Mexica people, the Aztec city Tenochtitlan was established to the east of Lake Texcoco. The Mexica people built ‘chinampas’, a construction method which raised artificial islands while allowing water porosity, and hydraulic engineering systems to keep the seasonal changes in the lake’s water levels from flooding the city.

The effects of the Spanish conquest, has been disastrous for the balance between the city and the lakes. Following colonisation, the city experienced incessant periods of flooding. By the turn of the 17th Century, a plan was drawn up to finally resolve the water problem of the city: “El Gran Desagüe del Valle de Mexico”. Once completed, and with the economic developments of the 20th Century, the city’s growth exploded, sprawling across the dwindling lakes.

Today, the need for water has caused Mexico City to reach far beyond its borders, or even its surrounding states’ borders, to bring water to its inhabitants. The city transports water from hundreds of kilometers away, and hundreds of meters in altitude. And so, the borders of the visibly urban extend even further to create a ‘Hydropolitan’ region, often causing serious environmental and social issues.

THRESHOLDS, ATENCO & THE LAKE TEXCOCO BASIN

The site of the old Lake Texcoco Basin, now an isolated urban island in the North-East of the city, as Mexico City sprawls around it.

The existing condition of the neighbourhood’s relationship with the Texcoco Lake basin is catalogued below. The way that the city has surrounded the site almost feels like a moat – a barrier which cannot be easily crossed. Yet in the neighbourhoods, it is evident that people have appropriated and encroached onto Mexico City’s “moat”, often making the boundary spaces into carefully curated gardens in front of their properties.

CITY SITE CYLES

SITE RESEARCH

It is the nature of all sites and projects to be subject to the changeability of species, climate and season. This drawing aims to synthesise the research that went into identifying the key changes which Lake Texcoco undergoes.

24 HOUR CYCLES

Human need to be included in site cycles: not only are we also animals, but ones who have a serious effect on our environment. The main identifier of our cycles is the arterial road (57D) which runs alongside the lake, the human cycles can be assumed to be of 24 hours: morning and evening rush-hours are a given in most cities, but especially so in the famously congested Mexico City.

Equally, the residential indigenous birds of the lakes will undergo a similar routine, waking, feeding, mating and sleeping in this period.

48 HOUR CYCLES

A healthy culture of Spirulina can double in size every 48 hours or so, meaning that harvest can be done every second or third day sustainably. The Wetland Centre, with its Spirulina production can introduce a new facet to human cycles, interesting to think that a cyanobacterium can introduce a different routine to locals. As the key demographic who stay in their homes, especially in disadvantaged neighbourhoods, women can be considered to be the main users of these spaces, the project will therefore be tailored to women.

6 MONTH CYCLES

Various migratory bird species use the reservoirs and lakes around Mexico City as a stop-over to their north-bound and south-bound migrations in spring and autumn respectively. Every six months, Lake Texcoco will become a flurry of birds, migratory and residential - with populations increasing as their breeding season goes underway throughout the spring and summer months.

GEOLOGICAL TIME: HUNDREDS/THOUSANDS OF YEARS(?)

Animal species are not the only ones which will experience cycles, the very earth that the city is built on will experience in geological time - the penetration and filtration of rainwater into the under-ground aquifers, which are currently exploited, and are causing shifts in the subsurface directly impacting the city above.

EXPLORATIONS FILM

Film served as a narrative tool to explain the historical conditions of water. The embryonic salamander motif which appears throughout the film is symbolic of the endangered Axolotl, indigenous to the area and once considered the form of a punished God by the Aztecs, which is now at risk.

It was important to show in the film the voices of Mexicans who are adversely affected by the water shortages and other issues as a way to communicate the serious socio-economic and political ramifications. María Guadalupe Moreno, who is an inhabitant of the poorer Iztapalapa neighbourhood in the North of the city is one of countless women who have no choice other than to wait for the “pipas” (water trucks) to arrive and deliver. Statistically It is the women who wait for the trucks, not the men. This is not an inconvenience, the unpredictability of the trucks means many of these women cannot get jobs, which means they can be in precarious or dependent financial situations. Water is also a feminist issue. Either side of María, the explorative ink studies which were carried out show the cyclical and often unequal distribution of water of the city.

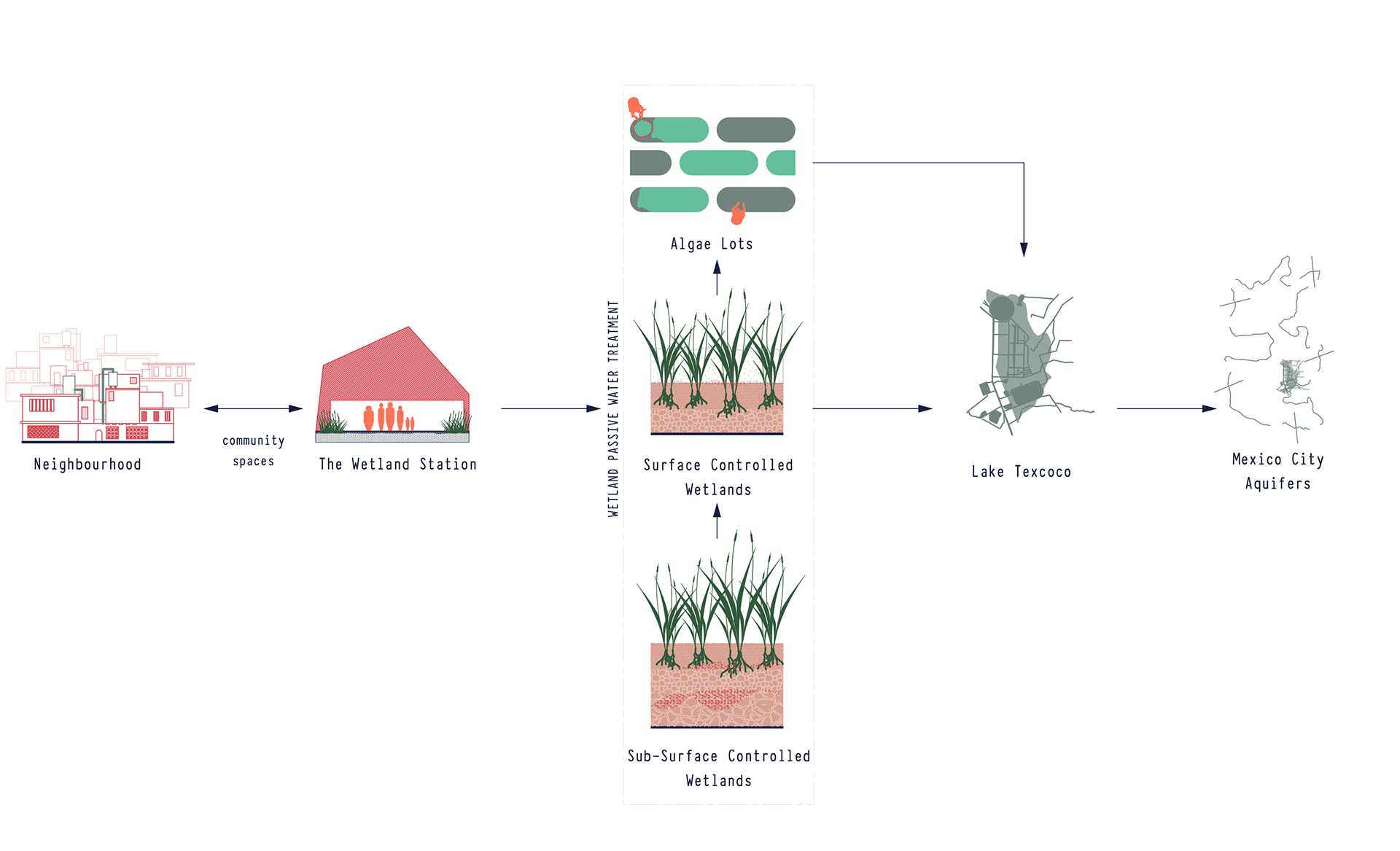

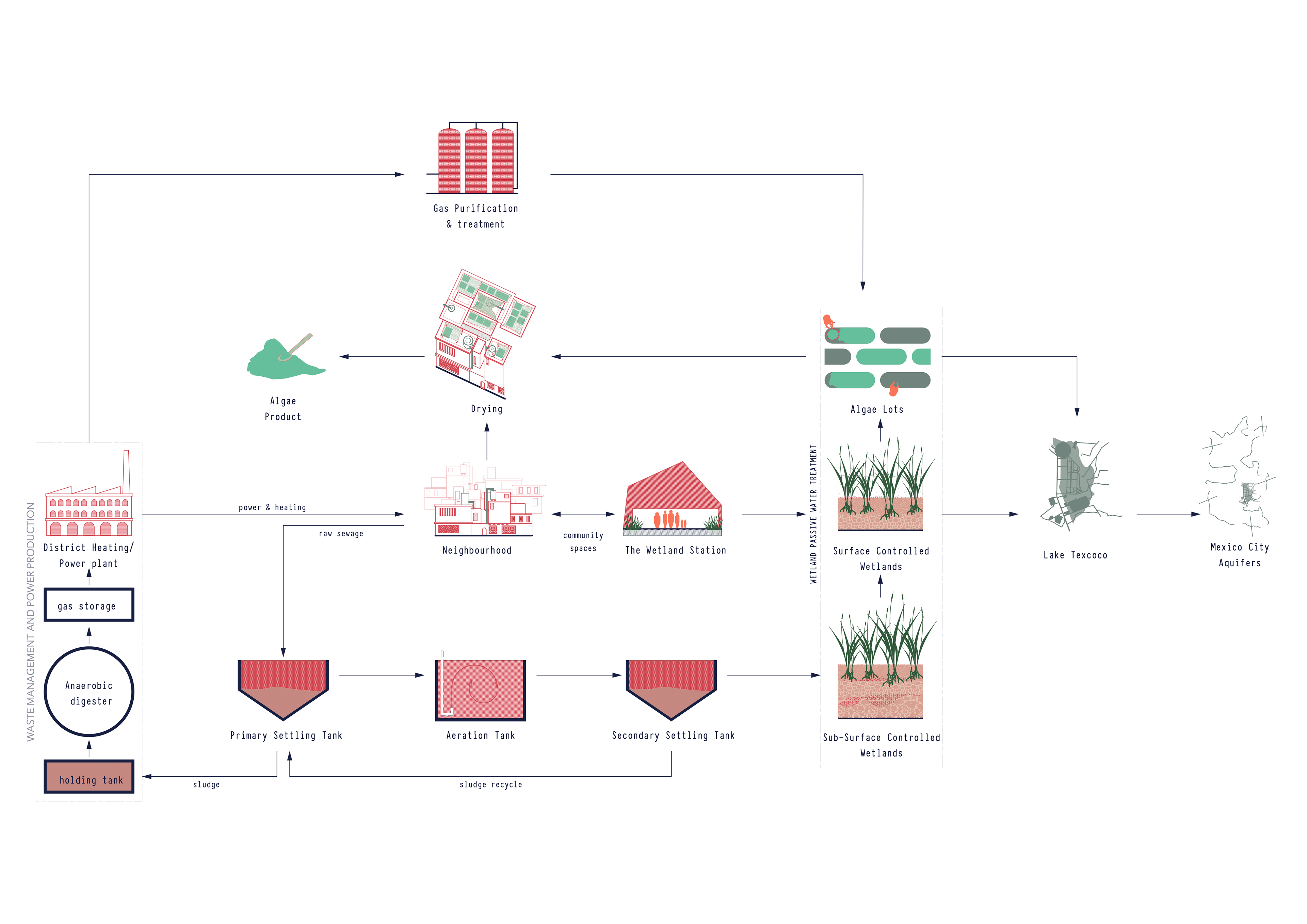

PROGRAMME

The scale of the old Lake Texcoco site calls for a diverse programme to inform any intervention which might take place. The diagram above shows the programme which will inform the project. The main goal from this exercise was to highlight the ‘symbiotic’ relationship between each element of the programme.

At the heart of the programme is the local community, the neighbourhoods surrounding the site tend to be low-income and often informal or illegal settlements. These come with a wide range of socio-economic issues, some of which might be able to be addressed by the programme and not ignored. With any development which involved a body of water in a city, the area quickly becomes gentrified due to the economic forces at play. By making the community an essential part of the programme for it to work, it can be hoped that the brutal gentrification and eviction which often occurs in informal settlements might be mitigated. One of the ways which this could be achieved is with a new housing typology, which allows for the processing of spirulina and creating community spaces which act as a bridge from the neighbourhood to the re-established Lake Texcoco.

These community spaces would be included in and around the “Estación del Humedal”, or “Wetland Station”. The purpose of which is to manage, maintain and investigate the re-established wetlands and Lake Texcoco, creating a locus of education, employment and leisure in this rejected part of Mexico City

Further to this, the waste from the primary water treatment before the wetland water treatment can go on to serve a District Heating Power Plant which would provide energy to local homes and to the programme itself.

The scale of the site allows this programme to be replicated along its boundary instances, in “satellite” sites working together but looking at different areas of the site, which will have inherent differences of urban contexts. However, for now the focus will remain in the north of the site, with the part of the programme focused on the community spaces of the Wetland Station which bridge the neighbourhood with the re-established lake.

CITY BLUE

URBAN EXTENTS

The Wetland Centre has been designed as one part of a wider urban strategy, with the ultimate goal to re-establish a more equal relationship between Mexico City and its historic relationship with water.

As part of my brief in the first semester, a symbiotic relationship was established between The Wetland Station and other programmes, such as a district heating centre, so that the longevity of the project would endure.

The following drawing establishes provisional positions within the Lake Texcoco basin, of some of these programmes, as well as additional ones: solar power farm, recreational lake use, tree planting, chinampa agriculture.

Due to the heavy use of concrete for The Wetland Centre, a material which is the main contributor to carbon emissions in the building industry, provision for a large area to become planted with indigenous trees has been made to the south of the site. This would be in conjunction with current “Water Forest” (Bosque de Agua) efforts by environmental organisations within the city.

In order to increase the personal stake of keeping the Lake and Wetland, a recreational area has been identified also, as a beneficial economic opportunity for the area. Crucially, it is important to highlight that nothing can change with a single one-off project. The true success of the overarching goals of The Wetland Station can only be reached if the intervention is city-wide.

From this stems the connection of the water bodies in the city, as a nod to the Aztec traditions and as a way to bring consciousness of water to the urban population. Much like the “green belt” surrounding London, this can be considered as a “Blue Bridge” which carves out space in the urban for human-animal ecosystems, as well as aiding in restoring the exploited aqueducts.

THE WETLAND CENTRE

DESIGN DEVELOPMENT

FILM SKETCH

FILM SKETCH

SKETCH PAPER MODEL

SKETCH MODEL

FILM SKETCH

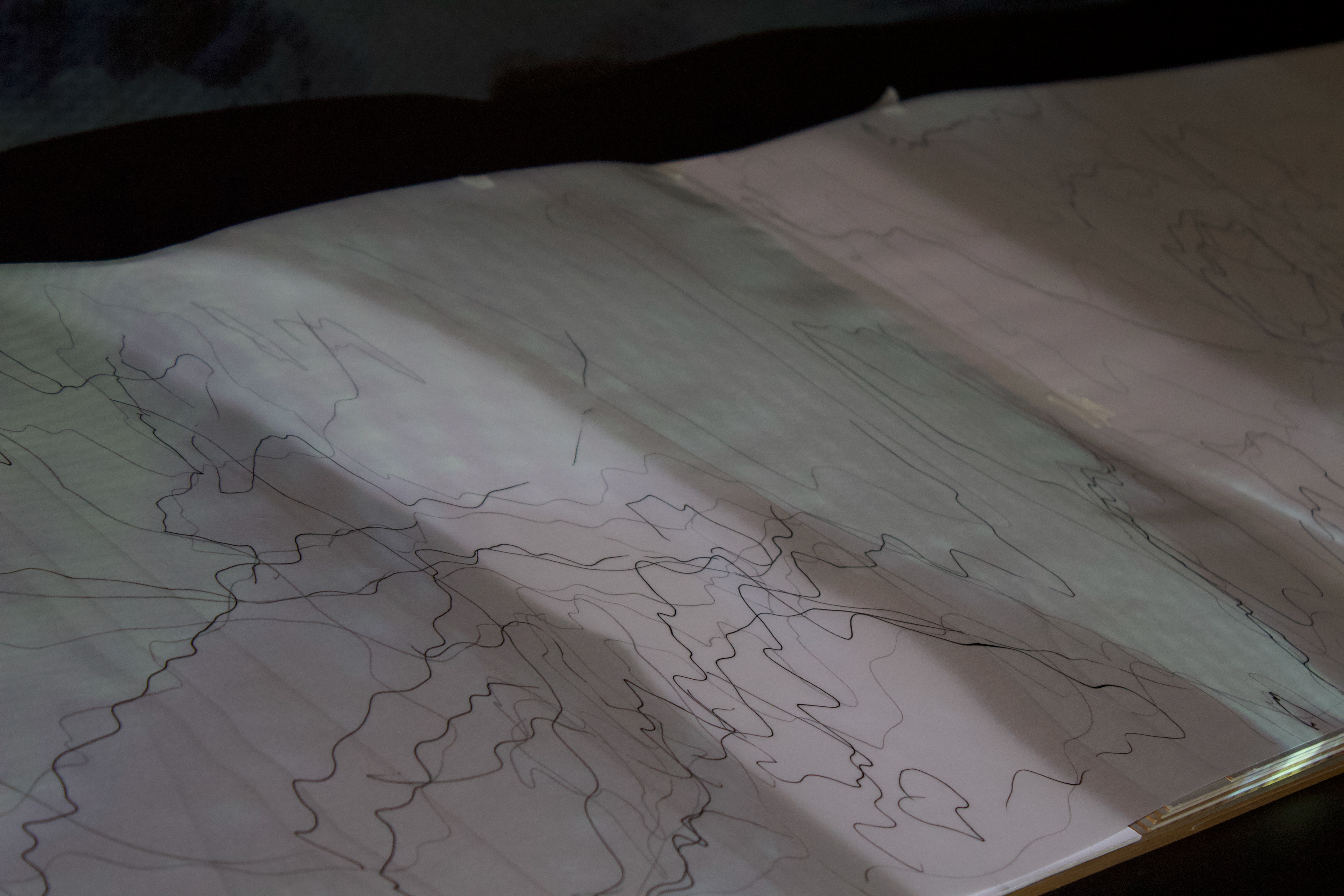

In order to break down the boundaries of the threshold of between the site and the neighbourhood, the film of the ink studies were projected onto the site model, and the boundaries of the absorbed ink traced on top of the site. Following this, areas were built up or bridged in key moments where there was a strong directionality to the ink growth or moments of intersection between ink stains. This informed the direction and flow of the design.

SKETCH PAPER MODEL

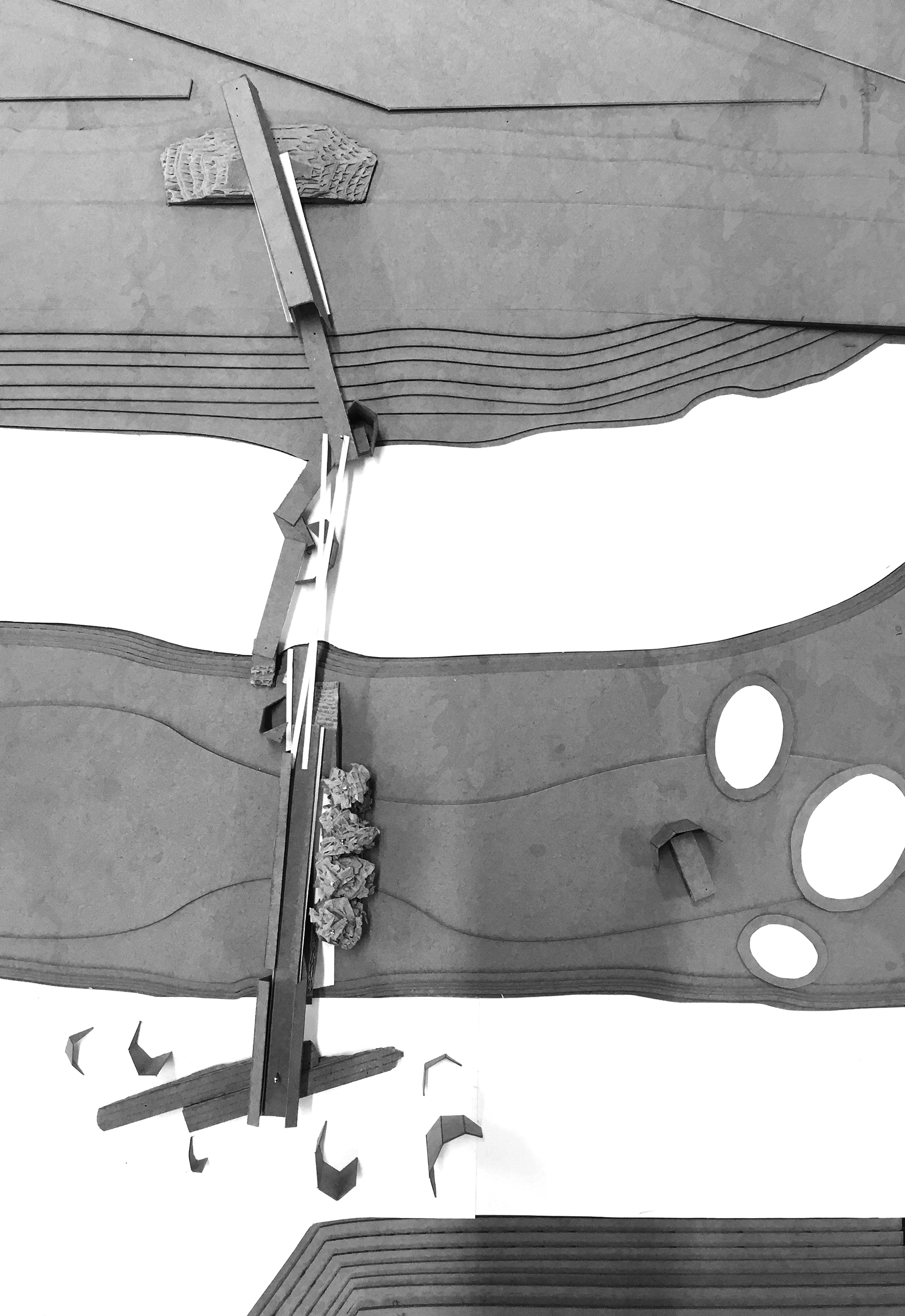

To begin to form an architectural language for the project a series of quick paper models were made to explore folding the thresholds to make connections or forms between the neighbourhood and the Lake. From these explorative models, the main architectural concept emerged as a tripartite of form: holding, spanning and wrapping.

SKETCH MODEL

A sketch model was then formed with the tripartite architecture in mind, to rationalise the architectural form and begin to carve out spaces for programme. Different materials were used for the tripartite of architectural forms: craft-board for HOLD, craft-paper for WRAP and white drawing paper for SPAN.

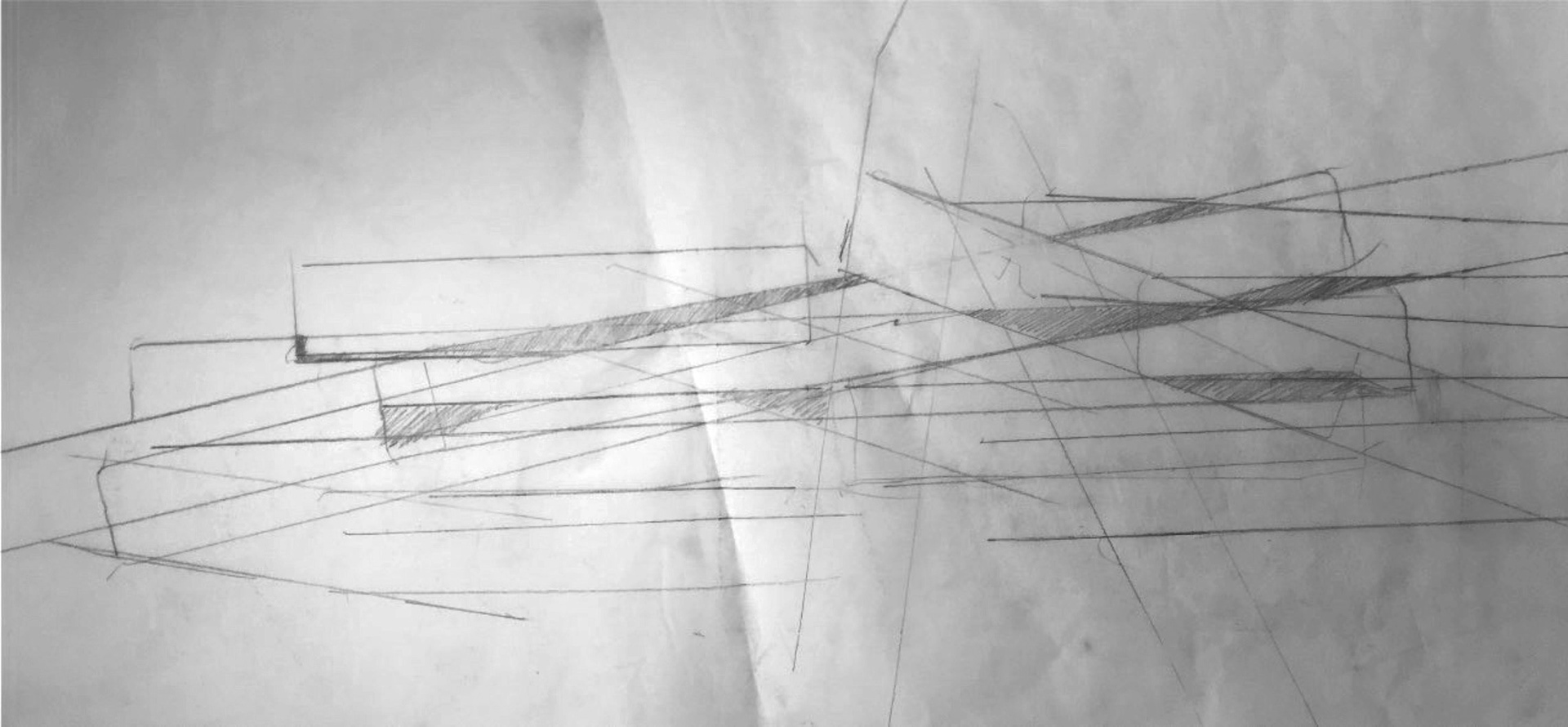

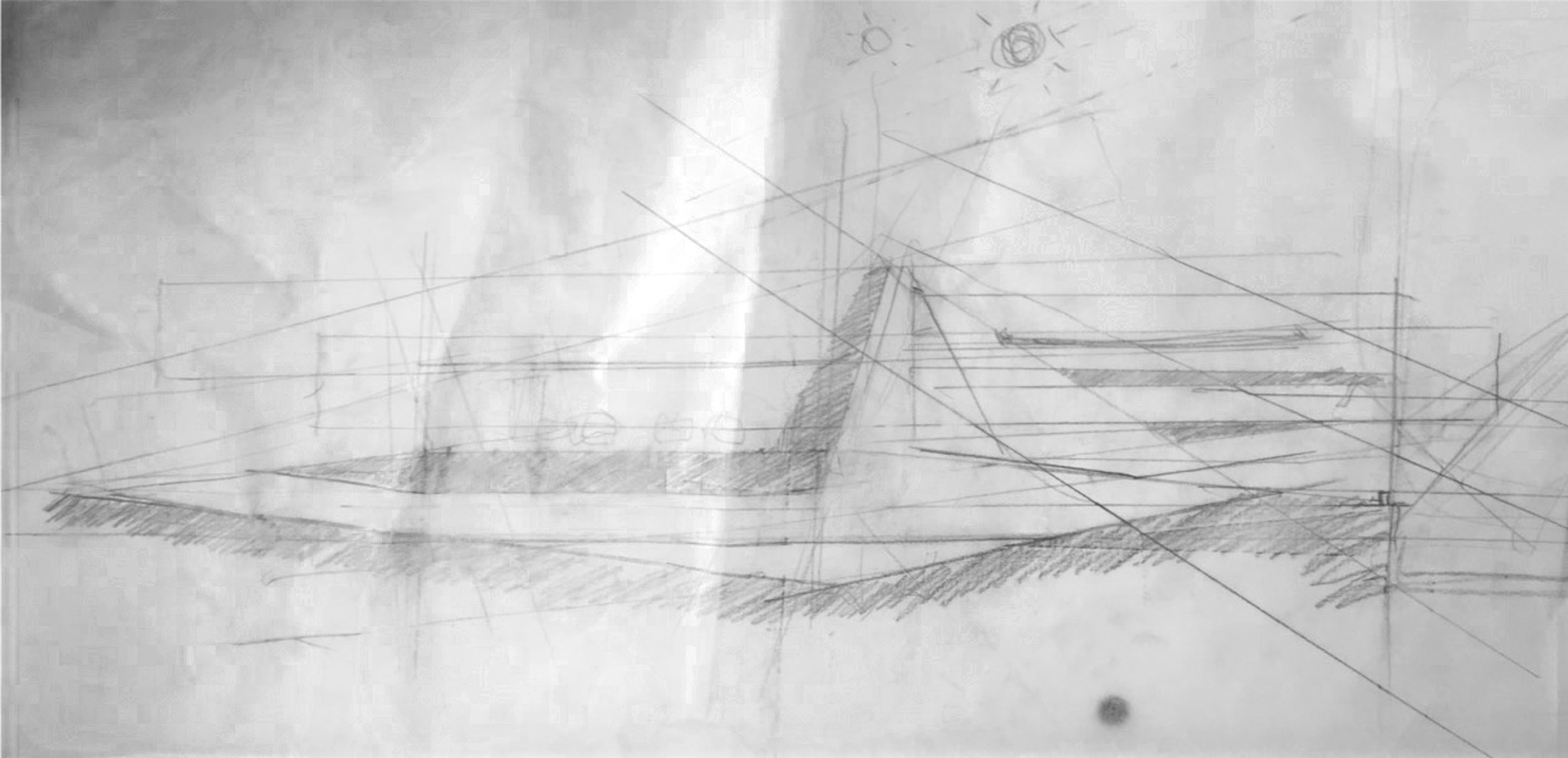

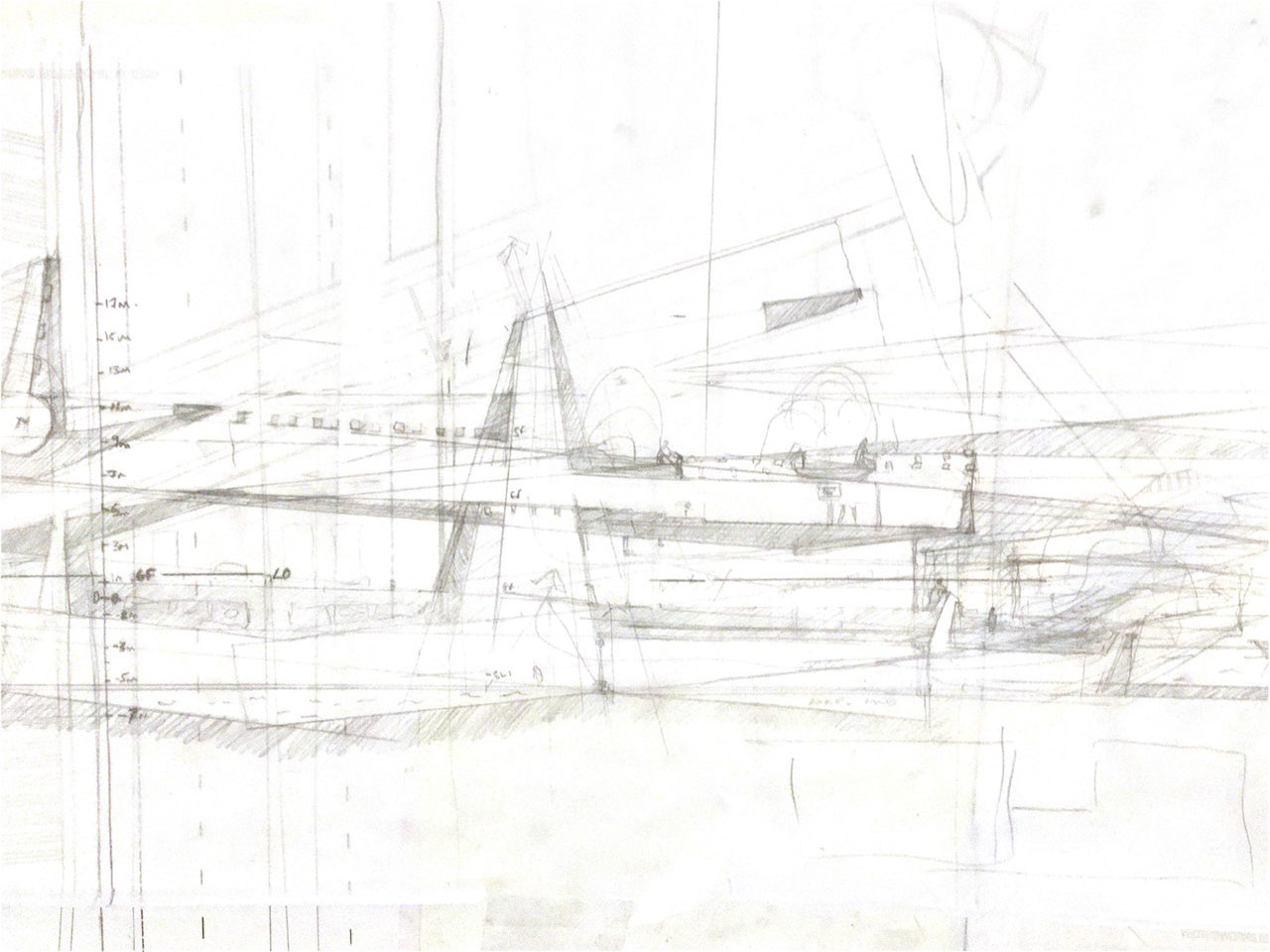

The architecture grew out an iterative process of drawing on large-format tracing paper at a range of scales, from 1:500 down to 1:100.

The drawings started with geometrically arranged lines, to give the following design a starting logic. From there, the overlaps and resulting forms were filled in to create a thickening of walls and spaces, which began to read simultaneously as plans and sections.

As the forms began to emerge, they were formalised, and tidied with every additional layer of trace. This is how the main cistern started evolving as an anchor to which the rest of the project moved around.

One of the more challenging aspects of this project was how to model it without losing the complexity of the hand drawn sections, plans and elevations, as the nature of 3D work is to ‘simplify’ to straightness.

I looked to achieve this by creating extrusions, from which subtractions were taken. These created interesting, resulting geometries. Though, using this method did complicate things further down the line when it came to detailing and formalising.

WILLOW WALK

SPIRULINA PRODUCTION

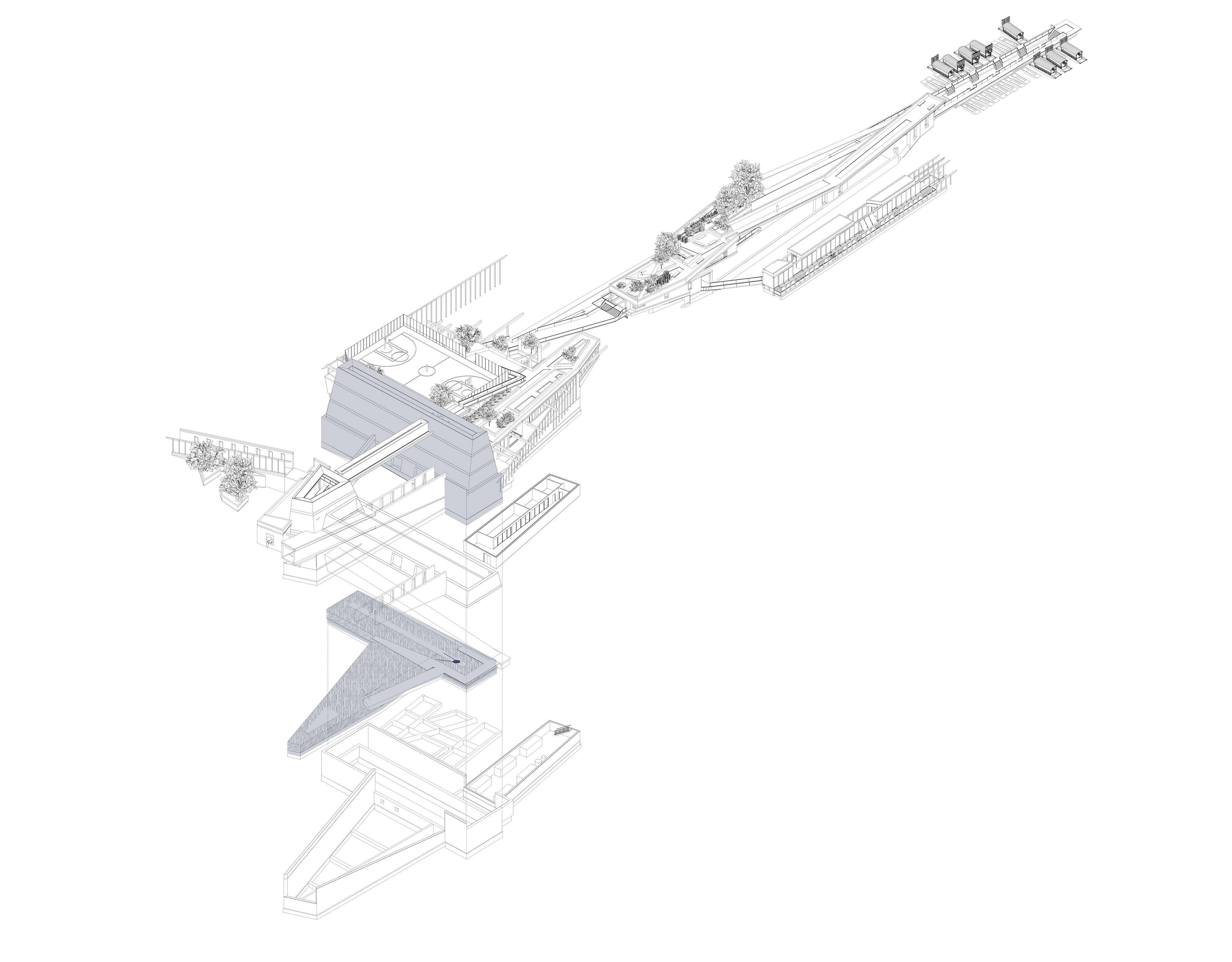

THE WETLAND CENTRE

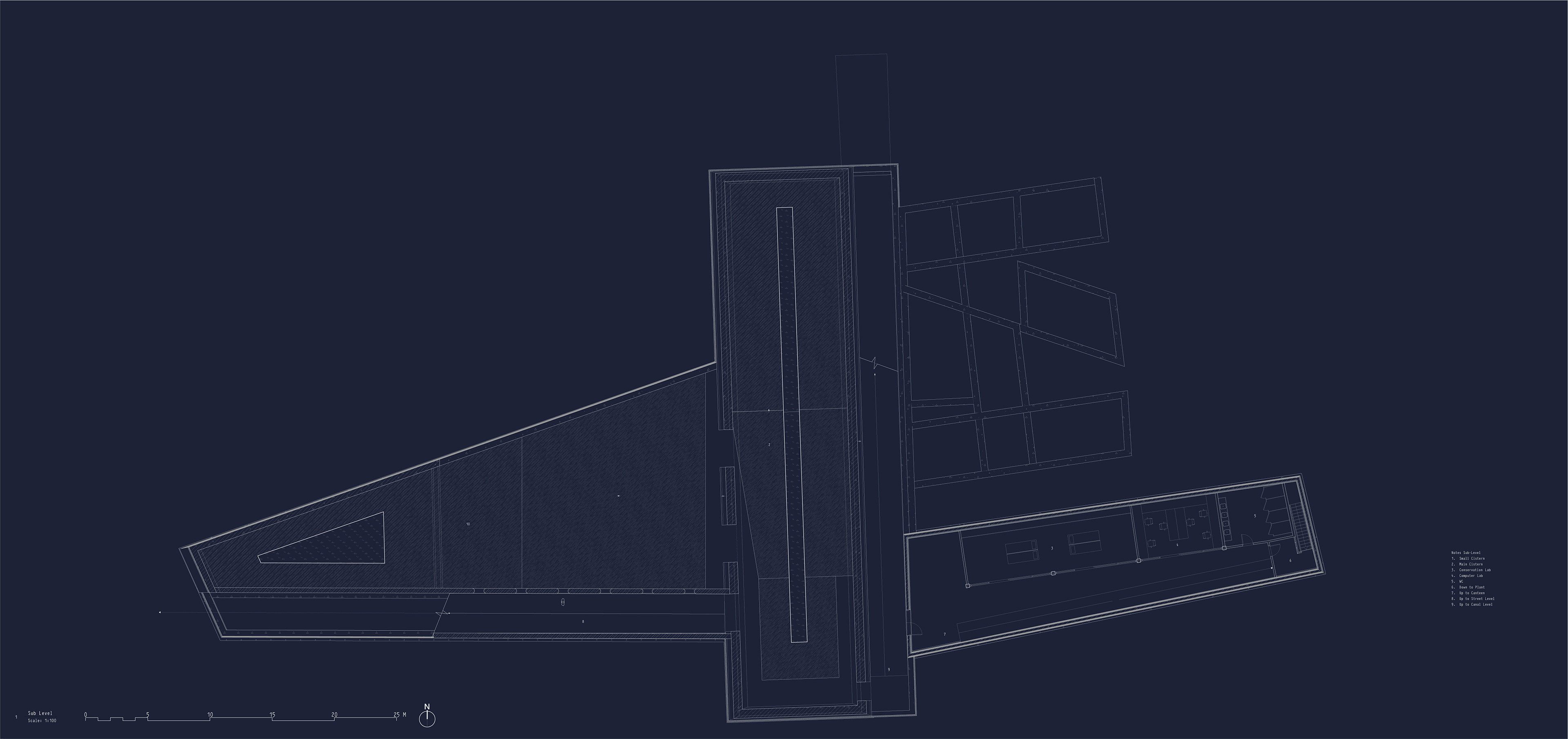

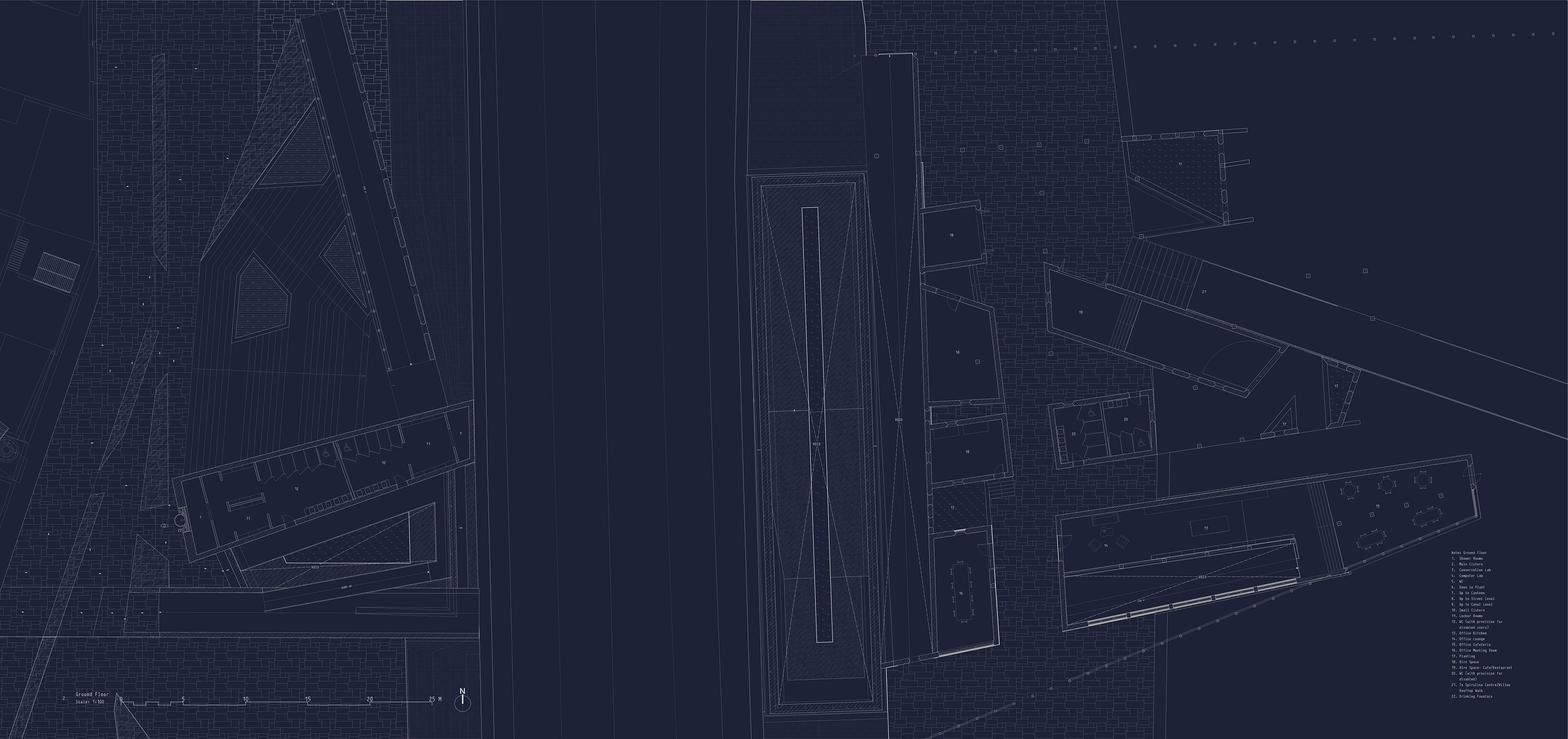

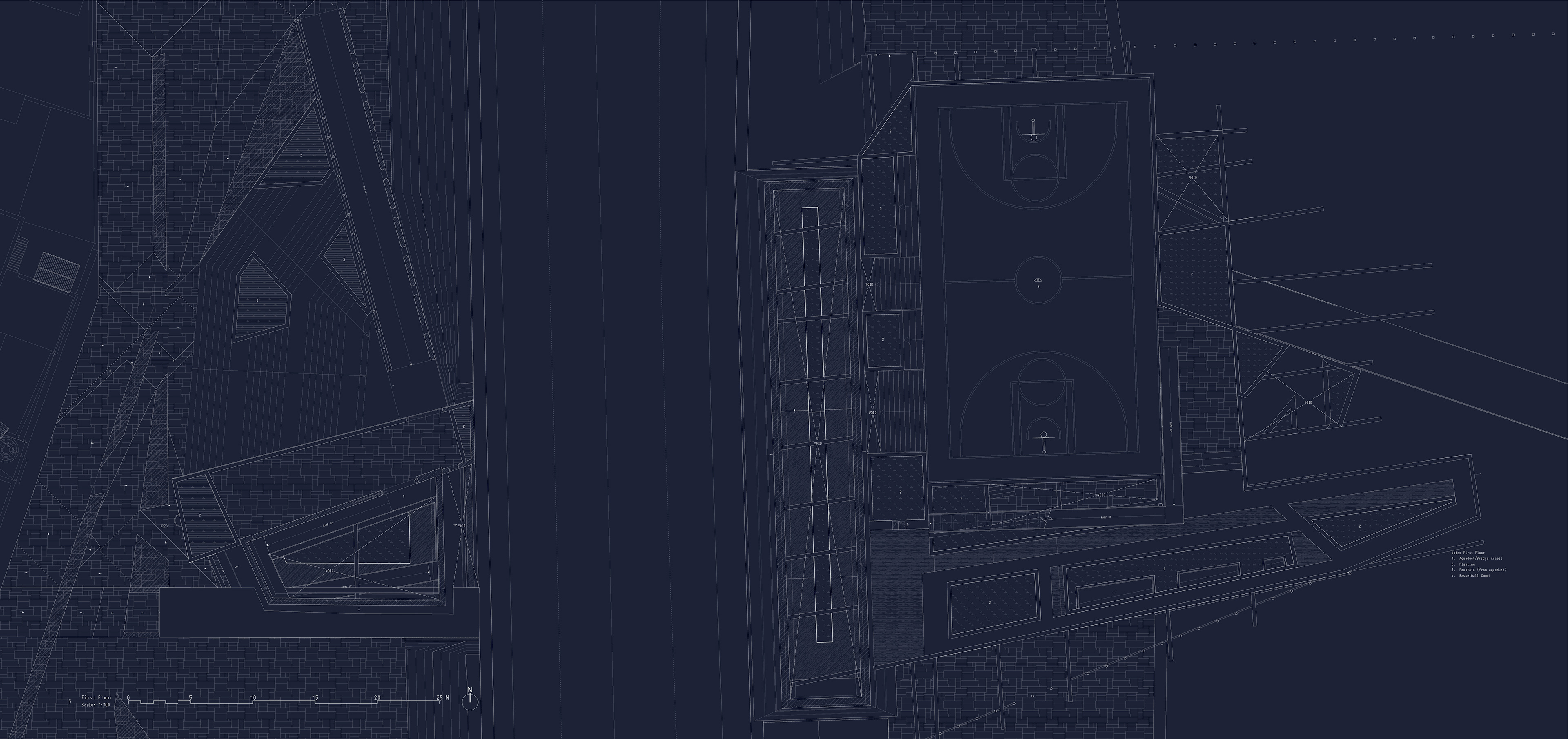

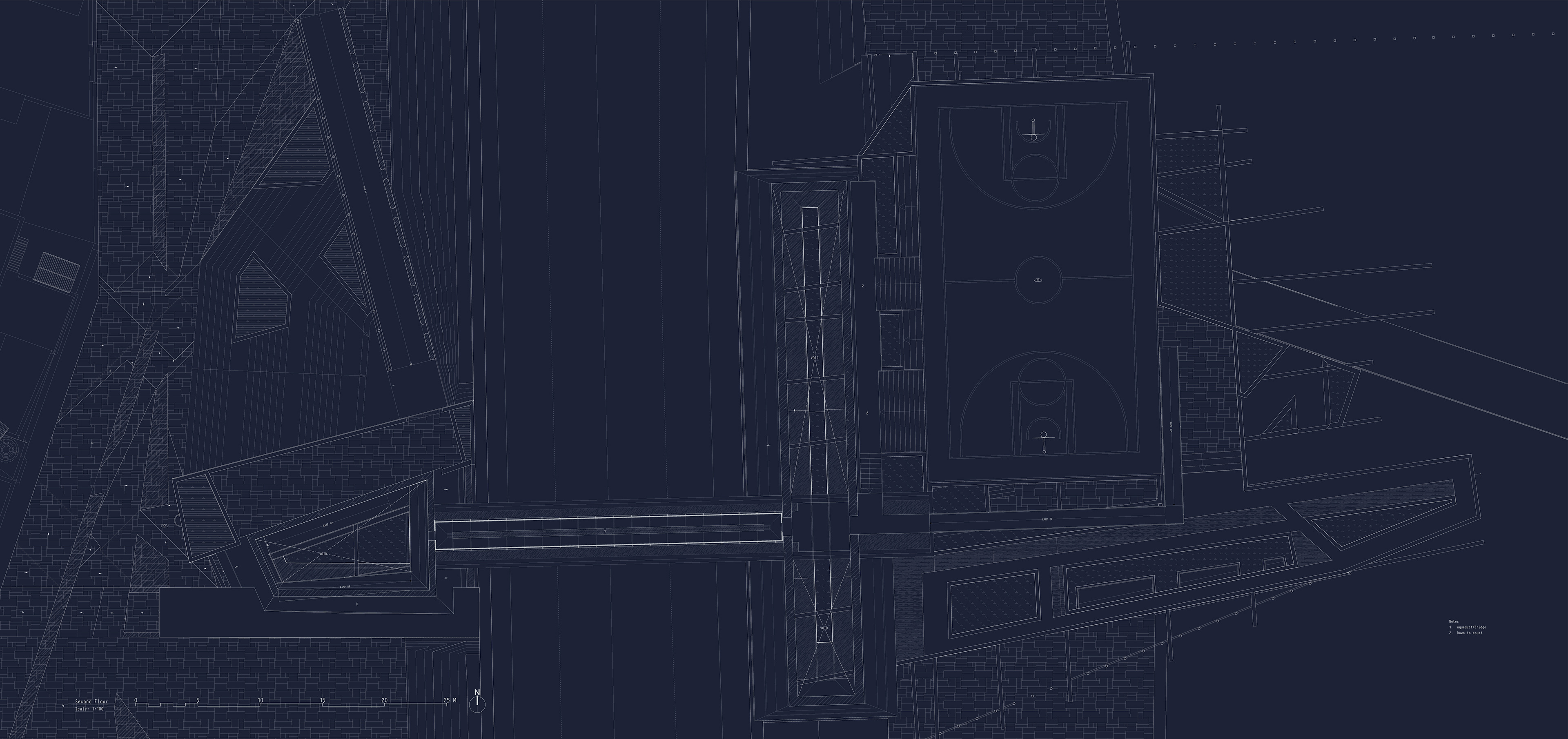

FLOOR PLANS

CISTERNS & THE WETLAND CENTRE

L -1/ Cisterns and Wetland Management

L 0/ Entrance level lightwells, changing rooms, Wetland Centre spaces, commercial canal-side spaces

L +1/ Public amenities: steps, basketball court, roof-top gardens

L +2/ Aqueduct Bridge over main road

SPIRULINA PRODUCTION

ENTRANCE & MAIN CISTERN

ARCHITECTURAL MOMENTS

Banyoles Town Centre, MIAS Architects

Banyoles Town Centre, MIAS Architects

Through detailing, it is possible for the project to extend far beyond its limits, and bring water into the neighbourhood in a safe and interesting manner. Inspired by the Banyoles Old Town refurbishment project by MIAS, water will be folded into the street paving.

The key part of the project, the main cistern marks the intersection between different users of the programme. This space not only serves as a water reservoir, but as a public swimming space. The reed bed in the centre of the pool acts as a natural filter. The rammed earth and concrete construction echo the infamous Mexican cenotes.

WILLOW WALK

ARCHITECTURAL MOMENTS

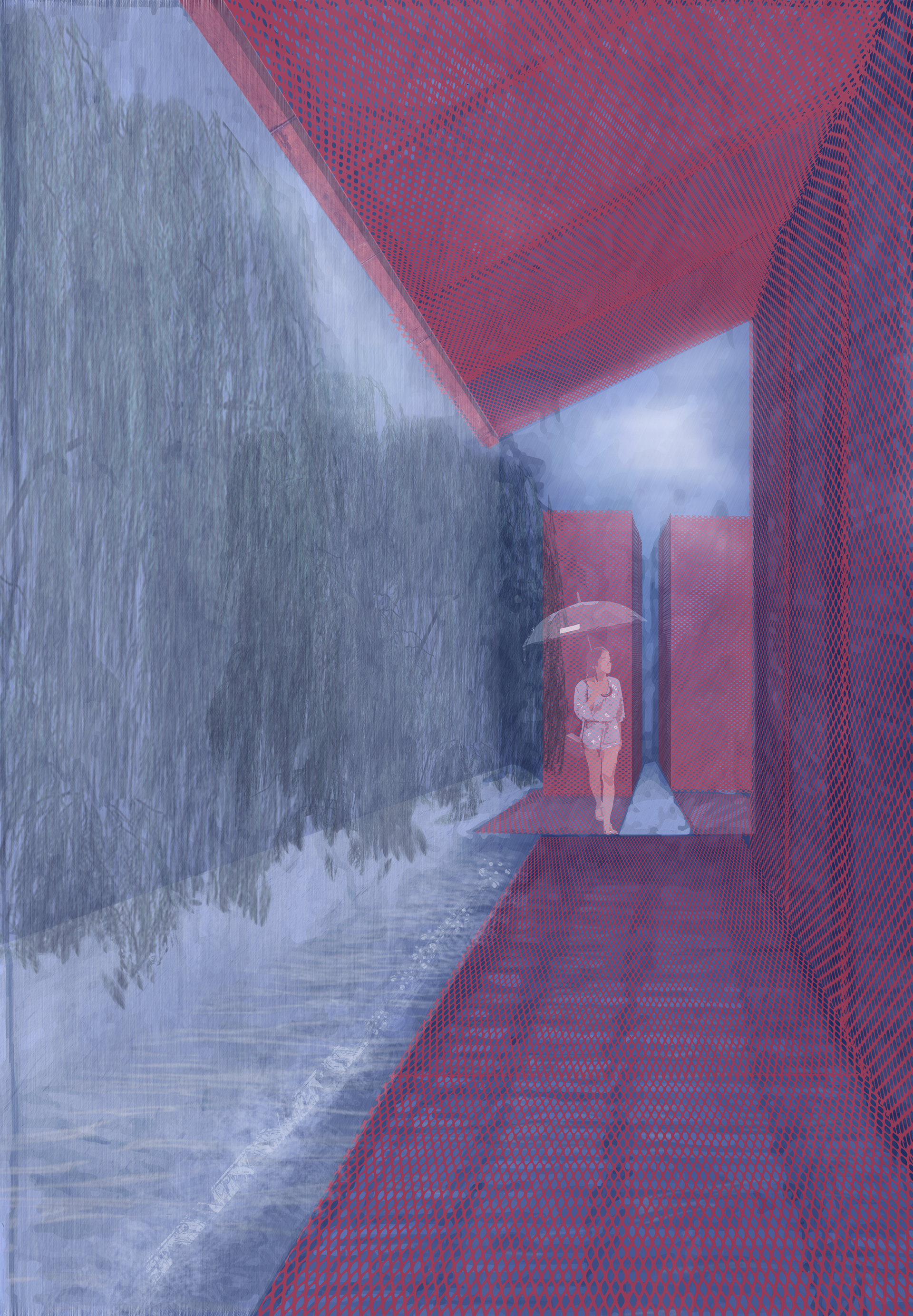

Stretching across the project is the red covered walkways and ramps, often found crossing the aqueduct. These are designed to be light-weight in construction to contrast with the concrete and rammed earth materials found in the rest of the project.

SPIRULINA PRODUCTION

ARCHITECTURAL MOMENTS

The processing wing has been designed with porosity in mind – from the ground that the workers will stand on, which will allow run-off water to return to the ground, to the open enclosed spaces. The idea behind this building is predominantly to provide shade and shelter, but to feel like an external space from which you can take in the beautiful views to the wetland.